- vita

- Sie sind hier: bibliography

- News

Skip to the navigation.

Skip to the content.

Nowhere else

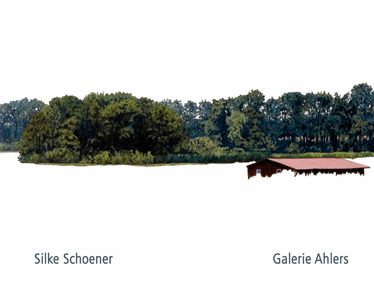

Dark shadows on the river from the trees on its banks. Shrubbery and bushes vanish in the dark – here and there the sun highlights radiant patches of color among the leaves. On the opposite bank, shades of green like olive, pine, apply, peach, and lime seem to light up in groups, patterned with walnut, amber, cinnamon, and sienna. The close cover of leaves on the bushes shows flickers of light. Water gurgles in the undergrowth and over the exposed roots, breaks on twigs and low-hanging branches. Now and then, a piece of flotsam gets caught in the branches, gathers more of its kind, and streaky wavelets spread over the water. It is cool here, sometimes in half-light, sometimes single golden rays of light flash through the branches to dance on the waves. Trickling, rippling, rushing. Between these banks, the river flows in its wide bed. It lies calmly in the bright sunlight, flowing majestically and slowly with a peaceful surface.

But there, where the river flows, Silke Schöner leaves a space in her painting “Alone”. She omits the river, the white undercoat of the canvas remains visible – only here and there, a faint pencil line indicates a previous detail that would have revealed more. When Silke Schöner paints, she always stops at some point – the rest remains white. She leaves out everything that she feels is not essential or necessary. Only the interesting, the part that appeals to her, jumps at her, finds it way onto the canvas.

Landscape painting is always the selection of a partial view into nature and habitat. The detail, which an artist chooses, indicates a corresponding interest. Painting in itself is selection, detail, point of view, perspective.

Nonetheless, the river is still there, marked and bordered by two beautiful wetlands – it places the observer into the painting, guides his thoughts onwards. The white space denotes the emptiness within, but also invites viewers to project their thoughts beyond the painting's rectangular surface. In the science of crystals, an empty space describes the vacancy within the regular arrangement of atoms, ions or molecules. Here, the perfect symmetry breaks up for a brief moment; the selective deviations change everything although the actual structure is maintained. Within the vacancies, the limits of the moments touch each other.

The expected orderliness is interrupted. At this point, the viewer is challenged to combine, to cross-link, to put into relation or – with a bit of courage – to leave it as it is. Without doubt, Silke Schöner has this courage.

She does not specify the mutual relations of the elements in the text. Something like the schoolboy whose answer to the essay subject "What is courage?" was the single intelligent sentence: “That is courage.”

In architecture, in landscape gardening, in reasoning processes or in self-administered organizations, empty space is interpreted as the greatest freedom and most attractive possibility. Here, one's own identity can be perceived and developed. How does freedom taste? One could reflect on the limits of freedom with Kant, because free spaces have clear conditions and stand in relation to each other.

But her levels are superimposed – here and there, new golden implications glitter across the surfaces instead of remaining silent. Silke Schöner defines the relations by terminating her work.

Similarities are found to typeset texts. Words and other items of information are separated or delimited by empty spaces; the size of the empty spaces within a piece of copy changes one's perception. In poems, it is self-evident that the empty space also speaks, makes an own statement that shapes the text decisively, condenses it. Also in painting, the times have passed, in which seemingly empty canvas is perceived as unfinished, infertile terrain. Free space is civilizing surplus, and intellectual freedom – a white space is not an index for emptiness, but for added value. Like walking barefoot across a shady, cool stone floor in the heat of summer, awareness is composed of different levels of perception. These levels can be widely separated.

Enlightenment and romanticism. White space and forest troll. The romantic landscape, which has idealized the forest as a metaphor and a place of yearning since the early 19th century, was intended as an inner dialog between painting and viewer – Silke Schöner's forest is different. Inevitably, one becomes immersed, but at the same time it is so epical that natural empathy or sympathy can be suspended in favor of reasoning. In the same way that theatrical landscapes drawn with chalk can create spaces, the empty spaces generate a trace of the unstated. White areas on a map. Regions, in which nobody has been before. In relationships, in families, things not said are often the most important, sometimes the most painful. The visible is that which can only just be vocalized. Which lies below the white surfaces. Which lies inside them. More than the unimportant. The world is not enough.

The moment that ends the creative act of painting is simultaneously a moment of pause. For a fleeting instant, the world is in balance, and with it the act of painting. A certain stability has been established. But that which is visible, is more than a stationary condition. At a small distance, there is something in the river – someone in the water. Further back, later, beyond the bushes at the river bend, a line of hills is visible in the distance, bright, light blue. Above is the sky, its surface left white. It is not possible to unhesitatingly fill the empty spaces with own content – they are not always so clearly self-explanatory. Shimmering between sky and earth, bouncing between heaven and hell. Each of Schöner's wonderful fine textures mirror a realistic surface in the artistic sense, an idealistic concession. The discoursed fissure between nature and culture, which has shaped its antagonists increasingly harshly ever since its inception, plays a role in the dispute about landscape painting, and in every landscape painting. Is it debatable? Does the increasing vulnerability and fragility of nature cause it to lose its entitlement? Does it go astray during the search for shape? Its fairy tales and myths break up, are renewed, fall into emptiness – where is my place?

Schöner's answers lead to a symbolic nature. Snow and water, the sky and wide-open fields sometimes form the undercoat of her places; elsewhere it is the light alone, Facades, shrubbery. The beautiful, precise artwork shapes the moment up to its climax, it picks out the sparks from it and dwells on it.

Not a single step back, no further. Here or nowhere.

Tina Lüers